Balkans via Bohemia doesn't do theatre reviews. But I found Washington Shakespeare Company (WSC)'s new production of Tom Stoppard's 1978 play Night and Day (which runs in repertory with two Tennessee Williams one-acts at Rosslyn's Artisphere through July 3) to be a moving and wonderful evening of theatre that did precisely what one imagines one of the world's best playwrights of ideas would want. It gave this audience member a lot to chew on.

The WSC's Night and Day is a production that effectively pokes at deep questions of morality in journalism and love and politics, and deftly provokes with sharp and sometimes savage dialogue that captures (but never reconciles) sharp divides in power and class. It's a play that people who love that theatre of ideas -- as well as journalists and foreign policy types who don't normally go to theatre at all -- should see.

And with Stoppard being Czech by birth? Well, it's a play that's squarely in the Balkans via Bohemia sweet spot.

Night and Day is not by any means Stoppard's best play. Stoppard's use of hairpin switchbacks between the interior monologues and exterior dialogue of Ruth Carson -- the play's only female character -- is among the most awkward stage gambits that the playwright has ever attempted. (Director Kasi Campbell and Abby Wood, who plays Ruth in the WSC production, make this odd device work as well as anyone could expect.) And there are glitchy patches of dialogue, especially in Act One, as Stoppard attempts to set his characters in this particular postcolonial milieu, where the play trips over an utterly (and unnecessarily) false moment or two and seems strikingly dated. (And, oh, yeah, the characters still rely on a telex.)

Yet WSC artistic director Christopher Henley made a very wise choice in presenting this much-neglected Stoppard play -- which premiered between the more highly acclaimed plays Travesties (1974) and The Real Thing (1982) -- to audiences in a city obsessed with power and journalism and scandal. The play wrestles wittily with moral conflicts and conundrums of journalism and sex that seem as fresh (and as blackening) today as the newsprint on this morning's newspaper. When battered and embittered Australian reporter Dick Wagner (played by in this production by Jim Jorgensen) sums up his vocation:

I am not a foreign correspondent. A foreign correspondent is someone who lives in foreign parts and corresponds,usually in the form of essays containing no new facts. I am a fireman. I go to fires. Swindon or Kambawe -- they're both out-of-town stories and I cover them the same way. I don't file prose. I file facts.

or when Ruth tidily dissects her marriage and infidelity:

Of course I loved him--loved Africa. Just like Deborah Kerr in King Solomon's Mines before the tarantula got into her camiknickers. And I haven't been a tart with Geoffrey. Slipped once, but that was in a hotel room and hotel rooms shouldn't count as infidelity. They constitute a separate moral universe.

the audience gets a sense of the power and playfulness of Stoppard's art.

But the best thing about Night and Day is that the play's power accelerates and aggregates as it heightens the stakes from the quicksand of casual affairs in the bedroom and political manuevers in the newsroom to an examination of the precarious foundations of the press in its relationship with power. President Mageeba of the fictional African nation of Kambawe (played here with smiling malevolence by Chuck Young) is Stoppard's wily and brutal amalgam of popular leaders turned dictators on that continent (and everywhere) -- a creature of menace and charm in not so equal measure, whose rhetoric at moments expertly plucks strings of popular discontent with journalism that infect even the most open of societies:

I did not believe a newspaper should be part of the apparatus of the state; we are not a totalitarian society. But neither could I afford a return to the whims of private enterprise. I had the immense and delicate task of restoring confidence in Kambawe. I could afford the naked women but not the naked scepticism, the carping and sniping and public washing of dirty linen that represents freedom to an English editor.

As Night and Day speeds to its denouement of death and its untidy epilogue of moral despair, crusty war photographer George Guthrie (played by Daniel Flint -- lead of Taffety Punk's production of my play Burn Your Bookes last spring) is left bloodied and only slightly bowed to hold up a flickering candle of the potential of news for good:

I've been around a lot of places. People do awful things to each other. But it's worse in places where everyone is kept in the dark. It really is. Information is light. Information, in itself, about anything, is light. That's all you can say, really.

The notion that vast moral darkness cannot entirely swallow up illumination is at the heart of Night and Day -- and also at the heart of the theatrical enterprise. It's wonderful that Washington Shakespeare Company is shining that light for the next few weeks.

Ticket information here.

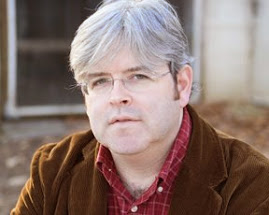

(Photo of Abby Wood as Ruth Carson in Washington Shakespeare Company's Night and Day.)

No comments:

Post a Comment